In the previous article I’ve described how to build the simple module to parse WebAssembly binary loader for the Ghidra. The module, I’ve created, contained a blank loader, blank analyzer, and placeholder for the processor. The only functionality it provided – verification of the header and suggesting the loader which will parse the input file.

In this article, I’m going to finish the implementation of the loader. I’ll tell how to parse a binary file and show its structure in human-readable representation, using WebAssembly format as an example.

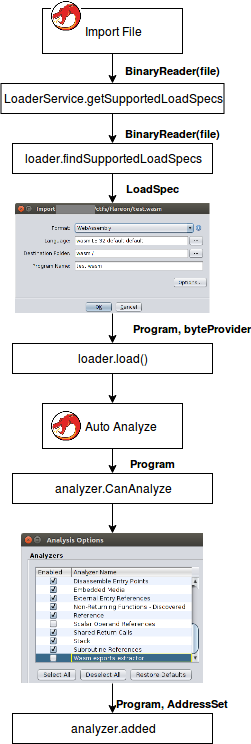

But before I dive into coding, I propose to review the workflow of file analysis and understand what callbacks Ghidra provides to the developer. I’ve learned it, studying sources of ghidra and recommend to do this to everyone who wants to develop his own module. Sources are clean to understanding and easy to read.

After the user creates a project and chooses what file he wants to import, Ghidra passes the file to method getSupportedLoadSpecs of the class LoaderService. The method tries to find all possible loaders, that can process the chosen file. It gathers all the objects, instantiated from the AbstractProgramLoader or it’s subclasses (loaders) and calls the method findSupportedLoadSpecs from each of them. (I’ve already implemented this method in the previous article),

The method checks whether the loader can process a given file. If so, it returns an array of the LoadSpec objects. Each object contains information of those who will further process the file and what Processor will be used to disassembly instructions.

Ghidra takes the output of the query to LoaderService and uses it to fill the fields of import dialog, allowing a user to choose which loader Ghidra will use to process the file.

After the user chooses the parameters and clicks OK button, Ghidra calls the method load of the preferred loader. The method creates and returns an object of the class Program, which represents the memory, the symbols and the listing of the processed file. There are some template classes, inherited from the AbstractProgram, taking initial setup and initialization of the Program. I’ve decided to use AbstractLibrarySupportLoader as a base class for my loader, because, according to documentation, it “provides a framework to conveniently load Programs with support for linking against libraries contained in other Programs”. As far as binary contains an import section, it would be convenient to use this class to show import methods from there. An additional advantage that the class already contains the implementation of the program structure initializer and the only duty of the developer is to parse format and place it to the memory of the program. After program initialization’s done, the class calls abstract method load, which should be overridden by the developer in the subclass. This method allocates additional program memory, processes relocations and adds symbols. API process the following methods, that will come in handy:

-

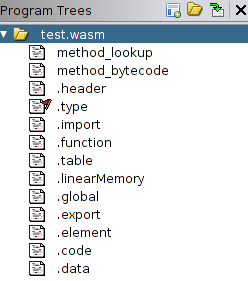

[MemoryBlockUtil.createInitializedBlock](http://ghidra.re/ghidra_docs/api/ghidra/app/util/MemoryBlockUtil.html). The method creates a block in the virtual memory of the program and fills it with the values from the source. Ghidra will show created blocks in the UI window “Program Trees."

-

[DataUtilities.createData](http://ghidra.re/ghidra_docs/api/ghidra/program/model/data/DataUtilities.html). It takes the structure, introduced by the object of [DataType](http://ghidra.re/ghidra_docs/api/ghidra/program/model/data/DataType.html) class, and applies it to the given address. Ghidra will annotate the data at the address according to the format of the structure:

-

[FunctionManager.CreateFunction](http://ghidra.re/ghidra_docs/api/ghidra/program/model/listing/FunctionManager.html). It marks range of memory as function. In the listing, ghidra adds headers before the addresses marked as functions.

Symbols, marked as methods, are exposed to the Function directory of the Symbols tree.

Symbols, marked as methods, are exposed to the Function directory of the Symbols tree.

Now, let’s see how is wasm format works and what information I can get from there to achieve the goal. Unfortunately, I’m not have too much time to implement everything, so I will focus on structures, helping to solve the challenge. But you can read the comprehensive description of the wasm format at this outstanding repository by Dan Gohman.

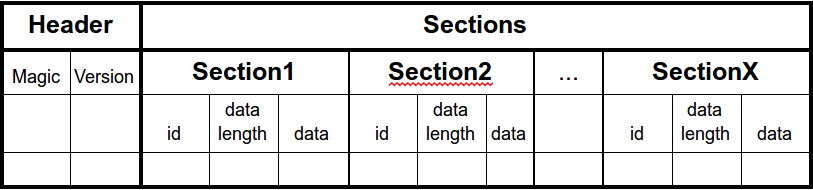

In high-level terms, structure of the wasm file can be represented by the following table:

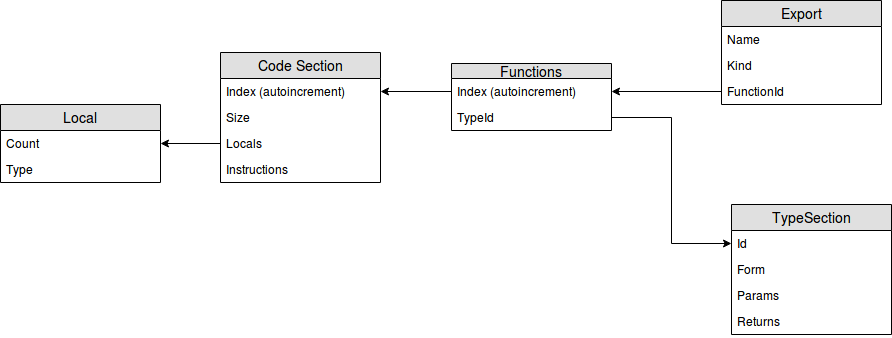

The file starts with a header, containing a magic identifier “\0asm” and a version of the file format. The header is followed by a sequence of sections. Each section includes an identifier, length of the data (in bytes) and, actually, data. The format of the data depends on the type of section. There are two categories of the sections. A custom section allows developers to extend the format. It has 0 in the id field and is out of the scope of this article. A known section has Id in range 1-11 and defined in the specification of the format. The most interesting sections from reverse-engineering perspective are those which contain metadata and instructions for the methods. I’ve represented them as entity-relation diagram:

Section Functions binds metadata from section Type and Export to instructions from section Code. Sections Exports and Type contain information about methods: name and parameters, while the entries from the section Code include code instructions. All the numbers in WebAssembly are represented by LEB128 format – variable-length format to encode integer values.

Now it’s time to implement obtained knowledge into the code. As usual, you can get the full code from the repository. In the article, I’ll tell stop on the code, essential to understanding the development process of the loader.

All the classes, describing the structures of wasm in my module consist of two parts. The first part is placed in the constructor and deserializes data from BinaryReader to java objects. The second part analyzes the data and returns a description of its structure. To build it, I make every structure class implementing interface StuctureConverter. The interface introduces the contract, obligating its subclasses to return the DataType object. This object later will be used to map structures to address space and make it human-readable.

The easiest example of this class is the header structure: it has fixed eight bytes size and only two fields: string magic and double word version.

private byte[] magic;

private int version;

//First part: constructor which deserializes data from

//input stream to java fields

public WasmHeader(BinaryReader reader) throws IOException {

//read magic string

magic = reader.readNextByteArray( WasmConstants.WASM_MAGIC_BASE.length() );

//read integer version

version = reader.readNextInt();

if (!WasmConstants.WASM_MAGIC_BASE.equals(new String(magic))) {

throw new IOException("not a wasm file.");

}

}

Method annotating this structure is pretty straight-forward. It creates an object of the class Structure and fills it with the information about fields. It uses the method add, creating the field in the structure. The method takes as arguments field’s type, size, and name.

@Override

public DataType toDataType() throws DuplicateNameException, IOException {

//create named structure

Structure structure = new StructureDataType("header_item", 0);

//the first item of the structure is a string, it’s size is four bytes

structure.add(STRING, 4, "magic", null);

//the second of the structure is a string, it’s size is four bytes

structure.add(DWORD, 4, "version", null);

return structure;

}

Later on, the structure will be passed to method createData, telling Ghidra, that data on the start of the program has a header format.

Address start = program.getAddressFactory().getDefaultAddressSpace().getAddress(0);

createData(program, program.getListing(), start, header.toDataType());

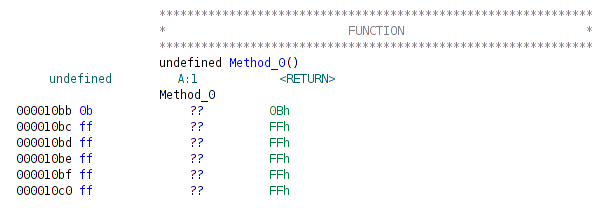

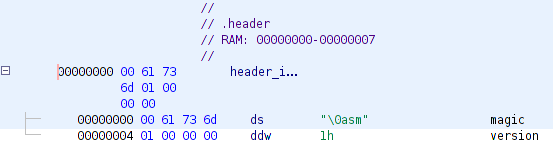

Result of execution of the code is on picture:

It works well for the fixed-size structures, but very often the size of a structure is variable and depends on data. As I told before, all the numbers in wasm format are encoded into the Leb128 format. A procedure, parsing this format, reads bytes one-by-one until it met byte, having a non-zero highest bit. In other words, the result size may be from one to five bytes. Processing the file, class Leb128 represents itself as one the primitive integer types, basing on data size.

@Override

public DataType toDataType() throws DuplicateNameException, IOException {

length = Leb128.unsignedLeb128Size(value);

switch (length) {

case 1:

return ghidra.app.util.bin.StructConverter.BYTE;

case 2:

return ghidra.app.util.bin.StructConverter.WORD;

case 4:

return ghidra.app.util.bin.StructConverter.DWORD;

}

return null;

}

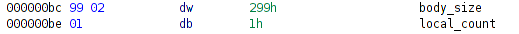

Let’s see how it works in the real world. For example, we have a structure with two fields: body_size and local_count encoded to Leb128 format

private Leb128 body_size; // 0x99 0x02

private Leb128 local_count; // 0x01

During initialization, they read their values from the BinaryReader object. Let’s assume that body_size has two-bytes lengths and local_count is just one byte.

private Leb128 body_size = new Leb128(reader); // 0x99 0x02

private Leb128 local_count = new Leb128(reader); // 0x01

As before, method toDataType creates structure, but instead of usage of predefined types and hardcoded length, it uses type returned by Leb128 object.

@Override

public DataType toDataType() throws DuplicateNameException, IOException {

//create named structure

Structure structure = new StructureDataType("function_1", 0);

//this time type and the length of the field is depends on data.

//in this case type of the body_size is WORD and size is two bytes

structure.add(body_size.toDataType(), body_size.toDataType().getLength(), "body_type", null);

//type of the local_count is BYTE and size is one byte

structure.add(local_count.toDataType(), local_count.toDataType().getLength(), "local_count", null);

return structure;

}

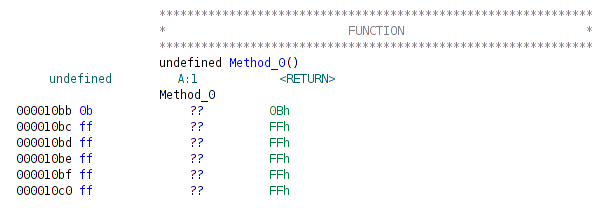

When this data type is mapped on data, it looks like that, correctly representing the variable LEB128 format.

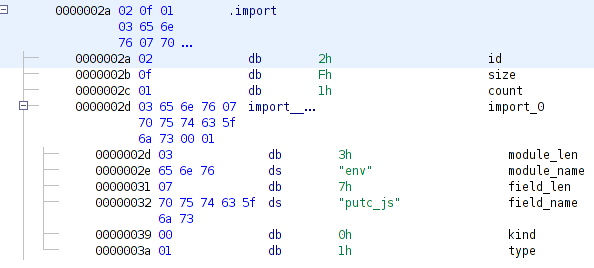

Code, parsing the whole section is a bit more complicated, but it is based on the same principle: it needs to create structure and add fields, considering that field can have composed type. I’ll demonstrate it on the example of the section Export. As every section, it starts with the header, containing id and size. It has a field, after the header, telling the number of entries and the sequence of export entries.

private byte id;

private Leb128 size;

private Leb128 entries_count;

private List<WasmExportEntry> exports = new ArrayList<WasmExportEntry>();

Export entry implements interface StructureConverter and returns its structure from method toDataType as well. Method toDataType of the class ExportSection takes the returned structure and adds it to its result, creating a hierarchical type.

@Override

public DataType toDataType() throws DuplicateNameException, IOException {

Structure structure = new StructureDataType("ExportSection", 0);

//adds field of primitive type, returned by Leb128 structure

structure.add(count.toDataType(), count.toDataType().getLength(), "count", null);

//adds to result complex structure returned by WasmExportEntry

for (int i = 0; i < count.getValue(); ++i) {

structure.add(exports[i].toDataType(), exports.[i].toDataType().getLength(), "export_"+i, null);

}

return structure;

}

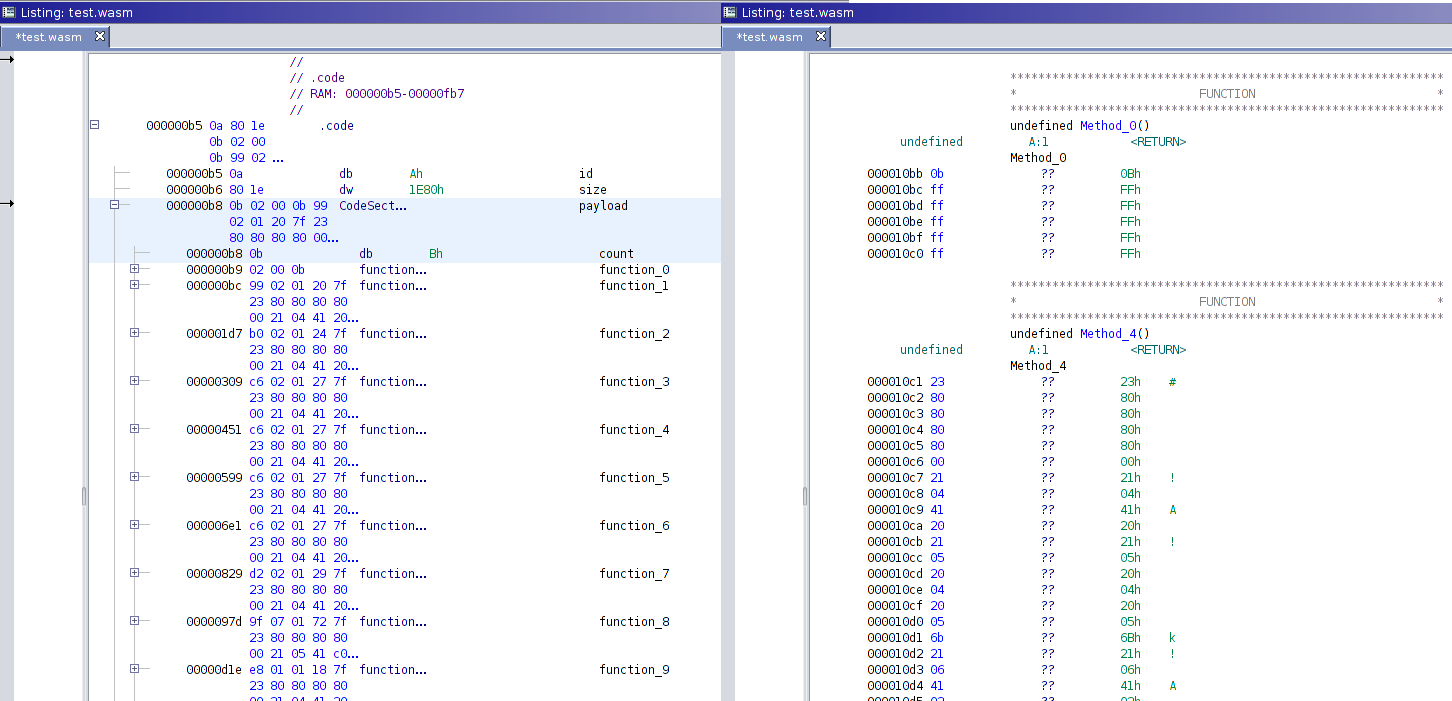

After mapping the structure on data, ghidra shows a hierarchy of nested structures. There’s a main structure .code, containing payload structure CodeSection, which in its turn includes structure function. Data became structured and easy to read.

The only problem is that instructions, marked as part of the structure can’t be decompiled. It’s a bit annoying because I’d like to have both, file structure and code representation of the file being analyzed. But in this case, it’s possible to find a workaround. The WebAssembly instructions are high-level and don’t operate addresses, calling methods by their indexes. Therefore, I can create one more “virtual” space for the code, and copy there the instructions of all methods contained in the application:

//Create a memory block for the instructions

Address address = Utils.toAddr( program, Utils.METHODS_BASE_ADDRESS );

MemoryBlock block = program.getMemory( ).createInitializedBlock( "method_bytecode", address, length, (byte) 0xff, monitor, false );

//for each method copy instructions to virtual memory

for (WasmFunctionBody method: codeSection.getFunctions()) {

long method_offset = code_offset + method.getOffset();

Address methodAddress = Utils.toAddr( program, Utils.METHODS_BASE_ADDRESS + method_offset );

byte [] instructionBytes = method.getInstructions();

program.getMemory( ).setBytes( methodAddress, instructionBytes );

}

It’s only left to mark each method as a function, calling the method createFunction, mentioned above.

program.getFunctionManager().createFunction("Method_" + lookupOffset, methodAddress, new AddressSet(methodAddress, methodend), SourceType.ANALYSIS);

So, at the and of the day I’ve built a loader, able to parse and annotate WebAssembly format. In the next article, I’ll try to implement WebAssembly processor, able to disassemble the code

Thanks to those who succeed to read the article till the end. Don’t hesitate to ask me in social networks, using contacts in the footer, if you have any questions about the module.